This site presents images of political graffiti affixed to the side of Santiago’s iconic San Francisco Church during the politically charged year of 2013.

Read the introductory essay below or browse the images here. And be sure to take this anonymous visitor feedback survey (only one required question) or contact the project’s author directly if you have any questions or comments!

Este sitio presenta imágenes de grafiti politico en el muro norte de la icónica Iglesia de San Francisco en Santiago de Chile en 2013, un año caracterizado por altas tensiones políticas.

Lea el ensayo introductorio abajo o aquí busque las imágenes. Y no dude en responder esta encuesta anónima para visitantes (solo una pregunta es requerida) o usa la siguiente forma para contactar a la autora con comentarios y preguntas.

Introductory Essay

Heritage practices function best when they recognize the multiple narratives which comprise any tangible or intangible monument. However, this inclusive approach toward heritage sites is complicated by graffiti vandalism, unsolicited practices which are often in tension with the monuments upon which they are inscribed. A striking example is the Reichstag at the close of WWII, where Soviet forces scrawled celebratory messages before exiting Berlin. Although these exclamations stand at odds with the nationalist identity of the former German parliament building, many of them are still preserved today.

Another instance of graffiti on heritage sites has stirred controversy in Chile’s capital, and has provoked a very different resolution. Polemic tensions have surrounded sprayed messages and glued posters (afiches) on the oldest colonial building in Santiago, the Church of San Francisco. First constructed in 1622 and renovated numerous times over the centuries, the church and its adjacent convent were officially declared a national monument in 1951. Since 1989, the northern exterior wall of the church has become a “blackboard of the people” for political debate and calls to action.

Strategically situated on a popular protest route along a primary artery called La Alameda, the barrage of political messages affixed to the north wall has solicited polarized reactions. On one hand, they embody free expression, particularly for those Chileans who feel that their voices are ignored by mainstream journalism. But on the other hand, this vandalism has arguably rendered the colonial monument “unpresentable” for the parish as well for tourism, and has been seen as unfitting for a national monument nominated to UNESCO World Heritage status.

During 2013, the debate between those in favor of maintaining the wall as a “chalkboard of the people” came to a head with those who viewed the graffiti as a form of historical and religious disrespect. This clash was catalyzed by a series of local events—presidential elections, on-going strikes, and the fortieth anniversary of the military coup which replaced President Allende with Pinochet—which motivated graffiti makers, or grafiteros, to cover the north wall in a torrent of political discourse. Those in favor of guarding the church as a national treasure struggled to comprehend why more had not been done to dissuade and remove this vandalism. More broadly, these texts continue to provoke critical questions regarding the role of graffiti on cultural heritage sites. Does their presence introduce new voices into an ongoing patrimonial project, or does it contaminate a site which was completed long ago? Is their damage merely superficial and temporary, or does such defacement, left unchecked, impact the character and quality of a historical monument in lasting ways? Finally, does the graffiti itself have intrinsic value as an alternative form of heritage?

Fanny Canessa V. and I attempted to address the tensions posed by the graffiti along the north wall in our article “‘Popular demands do not fit in ballot boxes’: Graffiti as intangible heritage at the Iglesia de San Francisco, Santiago?” [1] In this study we recorded and examined diverse first-hand viewpoints in order to weigh the historical, patrimonial, and religious value of the church structure against claims that its north wall best functions as a public “chalkboard.” Fanny oversaw student interviews carried out with parishioners and church staff as well as protesters and grafiteros; their findings underscored for us the vast divide between those who value the wall as a safe-harbor for free expression and those who view graffiti as denigrating to an important historic symbol.

Another aspect of this project was to record and examine the graffiti itself at critical political moments during 2013, noting its contents, its function as a call to action (to vote, to march, to resist), and named “sponsors” (usually political groups indicated as acronyms). Among these organizations, we found diverse student groups, presidential candidates, health reform activists, and indigenous rights groups. Unfortunately, within the limited space of the article we were unable to publish a broad sample of our documented messages in spray paint, stencils, and posters. This website is intended to serve as a companion site to our article, and as a space where we can present some of the now-eradicated north wall graffiti in digital form.

Humanities Commons as an Alternative Site for Graffiti?

One often-posed resolution to the problematic juxtaposition of graffiti at the Church of San Francisco is the relocation of these tags, posters, and stencils to a secondary site. Local authorities have suggested the re-institution of the walls along the Mapocho River, the location of well-known mural projects during the 1960s and 70s, as a renewed site for inscription.[2] Fanny Canessa’s students suggest the formal display of the marked walls with the “objective of reinforcing the idea of their existence and the validity of other positions….”[3] This website serves, in part, as a digital resource for preserving and exhibiting the graffiti of San Francisco, not in order to promote the vandalism of heritage sites, but rather as a straightforward exhibition site for these now-defunct messages. Certainly one may argue that their strength was directly linked to their original physical and cultural context, but the digital option has the additional benefit of circulating these ephemeral texts to new audiences.

The following stencils, sprayed messages and banners were recorded on the north wall of the Church of San Francisco during 2013, and many reflect upon or invite participation in aforementioned political events. All photographs were taken by Catherine Burdick on June 27 (in association with a series of national strikes), September 11 (the fortieth anniversary of the military coup), and November 14, 2013 (three days prior to the Chilean presidential elections which were won by Michelle Bachelet). These instances of graffiti can further conversations regarding the comparative merits of traditional (physical and historical) heritage sites on one hand, and one the other, the emerging role of new forms of semi-tangible and intangible heritage as open channels for free cultural and political expression.

Eradication: A Follow-up

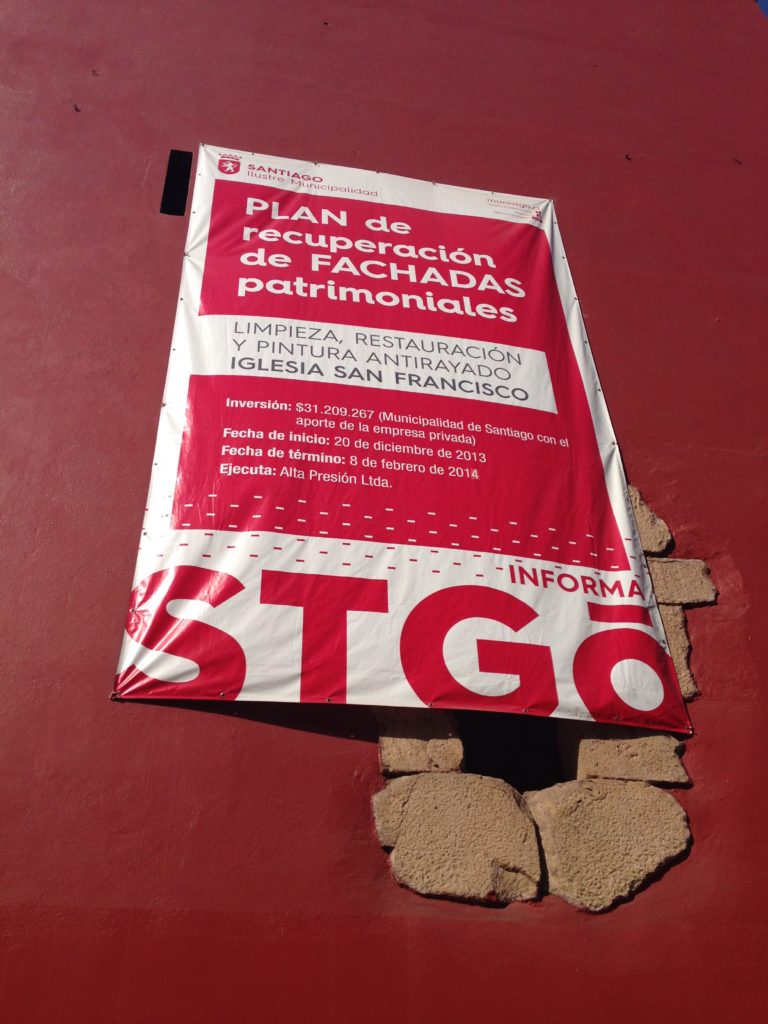

At the close of 2013 our article had been largely completed when the north wall graffiti became the subject of a heated legal debate which pitted the Chilean Supreme Court against the Municipality of Santiago. The Municipality, the official guardian of the city’s historical monuments, was eventually held responsible by the Court for the removal of all graffiti and posters, the reparation of the wall, and the application of anti-graffiti paint—all at a staggering cost.[4] The work was barely completed (see images below) when new graffiti was applied; the first arrests for vandalizing the north wall were made during the Workers’ March of May 1, 2014, but in this case the marks were quickly eradicated.[5]

[1] Catherine Burdick and Fanny Canessa V. “’Popular demands do not fit in ballot boxes’: Graffiti as intangible heritage at the Iglesia de San Francisco, Santiago?” International Journal of Heritage Studies 21.8 (2015), 735–756.

[2] Polémica por fallo de la Corte Suprema que obliga al Municipio de Santiago pintar iglesia San Francisco, El Mostrador (26 septiembre 2013), version on-line.

[3] Fanny Canessa V., with students Constanza Aravena, Paloma Ávila, Yasna Cabrera, Diego González, Francisca Khamis, Francisca Schmidt, Comunidades Contrapuestas: Muro Norte de Iglesia San Francisco, Santiago. [Communities in Conflict: The North Wall of the Iglesia de San Francisco, Santiago.] Unpublished results of the course “Comunidades del Patrimonio y Restauración Participativa,” [Community Heritage and Participative Restoration], Escuela de Artes, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, 2013, 57.

[4] “Trabajos comenzarán a fines de mes: Municipio de Santiago invertirá $38 millones para limpiar y reparar Iglesia de San Francisco,” El Mercurio (17 noviembre 2013), C1.

[5] “Masiva marcha de la CUT pasó frente a La Moneda,” El Mercurio (2 mayo 2014), A1 & C5.

Header photo: Abstracted view of San Francisco Church. Author photo.